DNB in trouble over Fishrot-related payments to Dubai

The Norwegian bank DNB ended its relationship with Icelandic fishing corporation Samherji after the fishing company gave what the bank deemed inadequate explanations of payments to three offshore companies and a company owned by the son-in-law of Namibia’s fisheries minister.

Documents filed in a Namibian court shed new light on why DNB closed the accounts of subsidiaries of Samherji last year. Last week, the bank issued a public statement saying that it had been warned it may be hit with a $45 million fine for not complying with money laundering regulations. The bank has been under police investigation in Norway since the Fishrot Files were published last year.

Last fall’s timeline is described in a document from Økokrim, Norway’s financial crimes investigation unit, which was shared with Namibian authorities this year.

The August 2020 report by Elisabeth Myre, an Økokrim investigator, details the start of the Norwegian investigation:

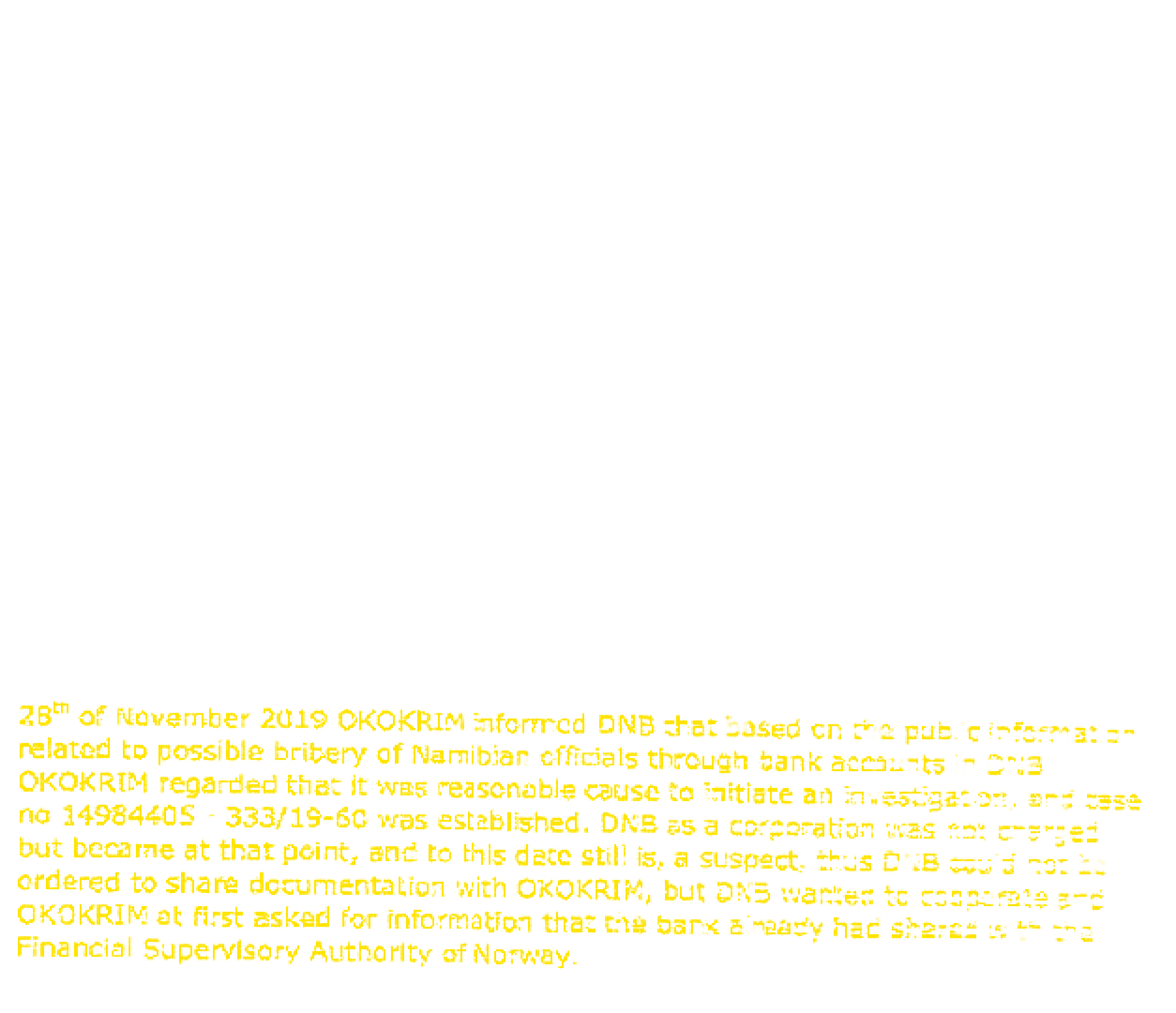

On November 28 last year, after Kveikur reported on communication between Samherji and DNB, Økokrim contacted DNB, telling the bank that based on “public information related to possible bribery of Namibian officials” using DNB accounts, Økokrim had determined that there was “reasonable cause” to start an investigation.

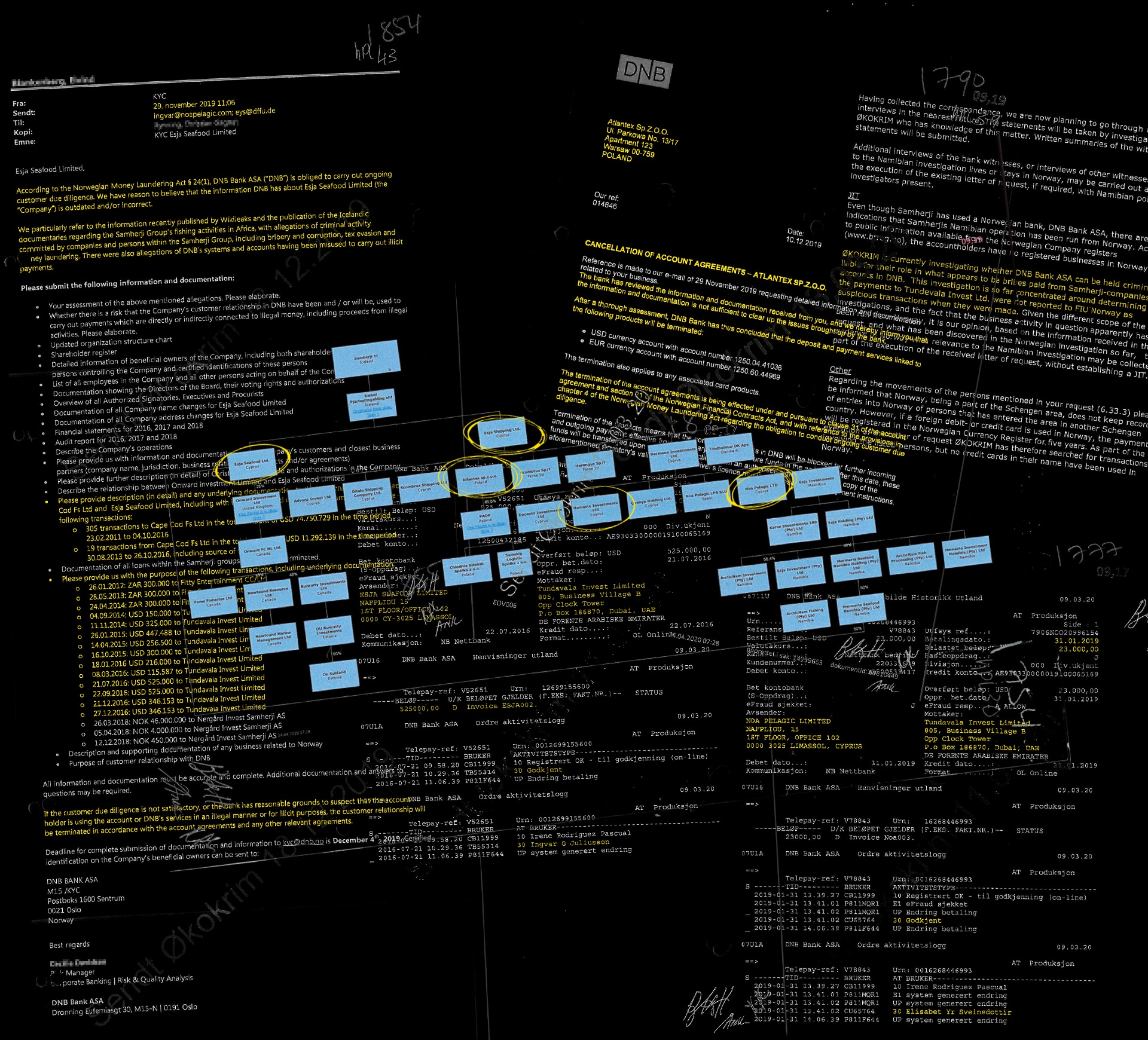

The Økokrim letter appears to have prompted the bank to take action. The next day, the bank wrote to four Cypriot companies—Esja Seafood, Esja Shipping, Noa Pelagic and Heinaste Investments—and the Polish fishing company Atlantex, asking the companies to explain bank transfers that had raised questions.

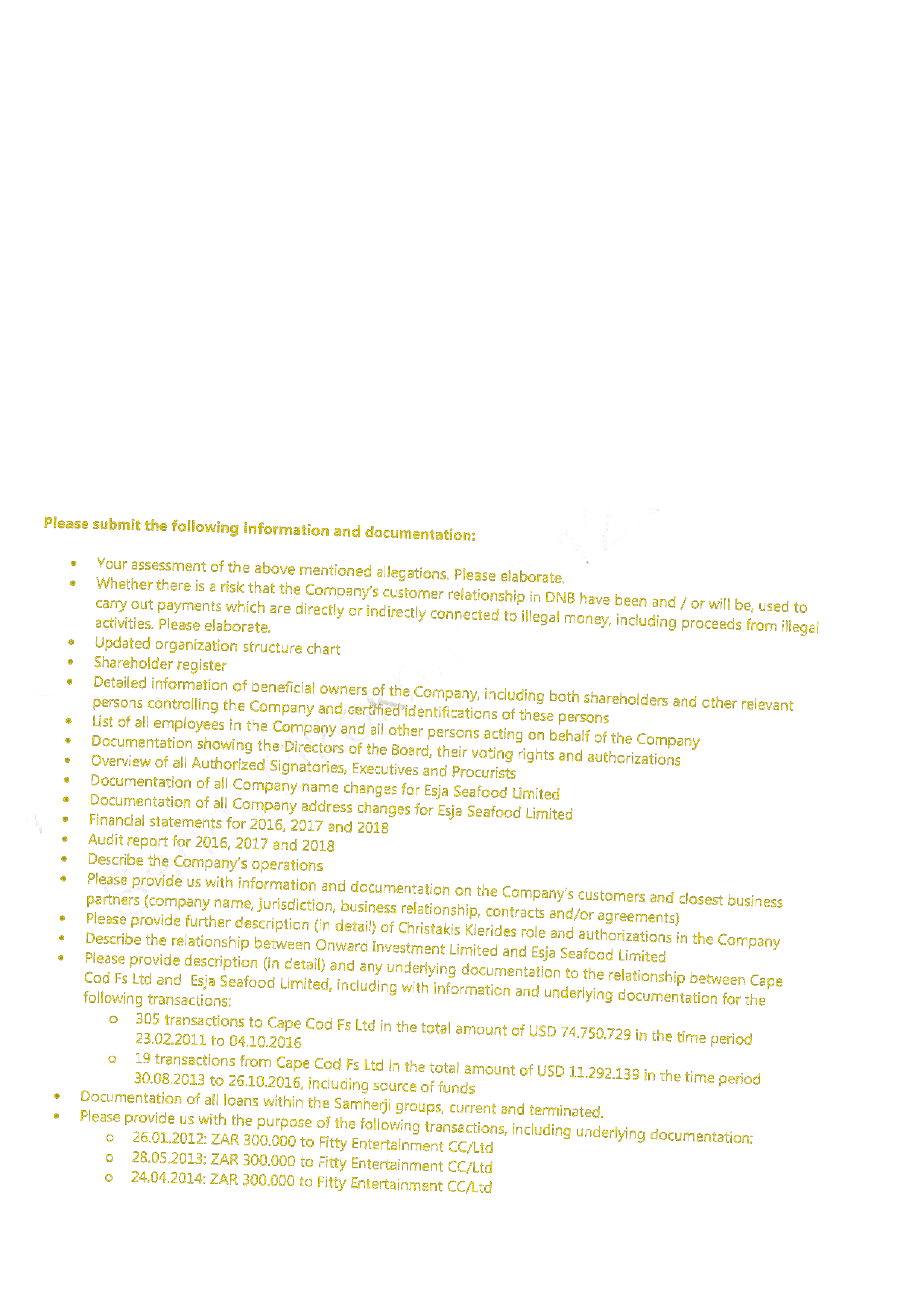

The letters to the five Samherji subsidiaries a DNB employee, stated that in accordance with Norwegian money laundering regulations, the bank was obligated to perform due diligence reviews of its customers.

“We have reason to believe that the information DNB has about Atlantex SpZ.O.O. is outdated and/or Incorrect.”

The letter refers specifically to Wikileaks’s publication of the Fishrot Files, and Kveikur’s coverage of Samherji’s alleged illegal business practices in Africa: bribery, corruption, tax evasion and money laundering—including accusations of illegal payments from Samherji’s DNB accounts.

The bank also asked the companies for information about financial statements, tax compliance and the directors of each of the five companies, as well as for a list of the companies’ largest suppliers and customers, and information about the purpose of those business transactions.

The response letters from Samherji’s subsidiaries are not part of the documents filed in Namibian court, but it’s clear that DNB did not think their answers were sufficient, since the bank decided to end its business relationship with the companies.

In letters sent to two of the subsidiaries, Atlantex and Noa Pelagic, on December 10 last year, the bank wrote:

“The bank has reviewed the information and documentation received from you, and we hereby inform you that the information and documentation is not sufficient to clear up the issues brought up by the bank.

After a thorough assessment, DNB Bank has thus concluded that the deposit and payment services linked to the following products will be terminated:”

As Kveikur reported last year, the revelations of payments from the DNB accounts of two Samherji companies to the company Tundavala Invest Ltd. in Dubai were one of the main reasons an investigation was started in Norway, Namibia and Iceland.

The owner of Tundavala Invest is James Hatuikulipi, the former chairman of Fishcor, Namibia’s government-owned fishing corporation.

Hatuikulipi was one of the so-called Namibian “sharks,” a group of government ministers, their family members and other influential Namibians who are now the subjects of a criminal investigation in Namibia, suspected of having used their power and influence to benefit Samherji, in exchange for payments that are investigated as briberies.

The Dubai-registered Tundavala Invest was central to the plot: Samherji paid the company millions of dollars over several years. On the invoices issued for those payments, they are described as consultant fees.

Emails and other documents from Hatuikulipi, the company’s owner, indicate that that was only a pretext. Namibia’s prosecutor general agrees. As reported by Kveikur this month, a Samherji employee and Hatuikulipi appeared to fear that the true nature of the payments would be exposed.

Each of DNB’s letters to Samherji’s subsidiaries last year lists specific payments from the companies’ accounts that the bank had deemed questionable.

The companies had previously reported to the bank in which countries they did business, but almost all of the transfers in question were made to companies located in unreported countries.

Companies that do business with DNB are required to regularly submit so-called company profile forms, where the bank asks for information used to assess the risk of money laundering or other illegal activities. One of the questions asked on the form is whether the DNB accounts will be used for business in countriesconsidered at higher risk for money laundering than others.

Offshore locations, where secrecy and low taxes often go hand in hand, are deemed particularly risky.

Therefore, DNB asks whether a company plans to transfer money to countries outside the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan or the European Economic Area. The director of Samherji’s subsidiaries answered “no” to that question. Still, the companies transferred money frequently and in large sums to places listed as high-risk for money laundering.

One of the companies, Esja Seafood, paid $3.5 million to Tundavala Invest in 11 transfers from the end of 2014 to the end of 2016, even as its director told the bank that the company would not be making such transfers.

On September 14, 2016, Ingvar Juliusson, a Samherji executive who was the director of the four Cypriot companies, signed a company profile form for Esja Seafood, answering “no” when asked whether the company would be making payments to locations others than the listed low-risk countries.

A week later, Juliusson transferred half a million dollars from Esja Seafood’s DNB account to Tundavala Invest. Two months earlier, he had transferred a similar amount to the Dubaian company.

There are no signs that any of the 400 DNB employees trained in assessing and analyzing money laundering risk acted at that point, or at any time earlier or later. Økokrim’s investigation of DNB is a result of that lack of action—the bank’s failure to report the transactions to the relevant authorities, as stated in an Økokrim letter to Namibian authorities in April.

“ØKOKRIM is currently investigating whether DNB Bank ASA can be held criminally liable for their role in what appears to be bribes paid from Samherji-companies bank accounts in DNB. This investigation is so far concentrated around determining why the payments to Tundevala (sic) Invest Ltd were not reported to FIU in Norway as suspicious transactions when they were made.”

Another DNB client, Noa Pelagic, also a Cypriot subsidiary of Samherji, transferred more than a million dollarsto Cape Cod, a company registered in the Marshall Islands, in 26 payments from 2015 to 2017. Noa Pelagic also made a $69,000 payment to Tundavala Invest in Dubai.

Just like in the case of Esja Seafood, Juliusson had stated to DNB that Noa Pelagic did not make any payments to countries others than those listed on as low-risk for money laundering.

Kveikur asked DNB whether the bankthought its anti-money laundering measures had been insufficient, or whether DNB believed Samherji had given it false information. Vibeke Hansen, a DNB spokeswoman, said that since the Samherjicase is subject to police investigation, and isrelated to a specific customer, the bank could notcomment.

Björgólfur Jóhannsson, one of Samherji’s two chief executives, said in a statement that the company utterly deniedhaving made improper use of DNB accounts. He also said the company did not pay any bribes or makeotherillegal payments related to Samherji’s operations in Namibia or elsewhere.

Jóhannsson said that DNB had been under investigation since December 2019, andhad decided to sever its business ties with Samherji at the same time. “Therefore, this story is a year old,” he said.

“DNB’s decision did not affect the operations of our companies. The decision in and of itself may however have been illegal.We believed we had given satisfactory answers to the bank’s inquiries.”

Additional work for the English version of the story by Tryggvi Aðalbjörnsson.